Greg Brown returns to look at an important thing relevant to first responders (and lots of other people really) – the sucking chest wound.

We’ve all been there – sitting through some kind of “first aid” training and having some kind of “first aid trainer” speaking authoritatively on some kind of “first aid style” topic. If you are like me you’ve used your time productively over the years and perfected what my wife refers to as “screen-saver mode” – it’s that look on your face that tells the instructor that you are listening intently, often supplemented by the insertion of “knowing nods” or head-tilts, but in actual fact you are asking yourself “if I was able to collect all of my belly button lint over a 12 month period and spin it into yarn, I wonder if I could make enough to abseil off London Bridge?”

Don’t get me wrong – I reckon effective and accurate first aid training should be a mandatory part of having a car / bike / truck / bus licence. More appropriately trained people should mean faster recovery rates for most injured people (and less work for overstretched first responders).

It’s just that sometimes first aid trainers teach stuff based on ‘we reckon’ or ‘that’s how we’ve always done it’ rather than evidence or knowing it works in the real world. This post is about one of those things.

“What is a sucking chest wound?”

In the Army questions come in a few different shapes and sizes. A popular one is “there is only one obscure answer you should have guessed I wanted”. Trust me, the muzzle velocity of your primary weapon is 970 metres per second.

Another popular one is “the question that should be about one thing, but is actually to demonstrate a quite tangential point”. Like,

“What is a sucking chest wound?”

For an army instructor the answer is not what you are thinking right now. It is “Nature’s way of telling you that your field craft sucks and everyone can see you and now you got shot”.

Let’s Go With the Medical One

We’re going to go with the alternative, more medical one. A sucking chest wound is defined as air entering the thorax via a communicating wound that entrains air into the space between the lungs and ribs more readily than the lungs can expand via inspiration through the trachea.

This is about pressure differentials – in order to inhale, the lungs must generate a relative negative pressure such that air can be sucked into them via the trachea. But if you make a big communicating hole in the trachea, that might become a pretty big highway for air to enter the space with the negative pressure.

The communicating hole does need to be pretty big. Depending upon which textbook you read, this hole needs to be a minimum of a half to three quarters the diameter of the trachea. Also, the patient needs to be undergoing relative negative pressure ventilation (or, in simple terms, breathing spontaneously). If they are being artificially ventilated (which requires positive pressure) then the pressure inside the lungs will be higher than the pressure on the outside of the body; the result is that air will be forced out of the intra-pleural space (or thorax) by the expanding lung (as opposed to being entrained into the thorax via the hole in the chest).

Are sucking chest wounds really that bad?

Well, yes. They suck in fact.

A sucking chest wound creates what is known as an open pneumothorax. Let’s consider the option where that hole does not seal on expiration. We’ll get onto the also very annoying sealing with a flap version in a bit.

In this slightly not so annoying case, the patient will have a ‘tidalling’ of air in and out of this communicating hole. The effect? Respiratory compromise, increased cardiovascular effort and reduced oxygen saturations. Patient satisfaction? No, not really. Death? Maybe – depends on what other injuries exist and the ability of the individual to compensate. See Arnaud et al (2016) for more details.

But if this communicating hole were to seal itself on expiration then you now have an open tension pneumothorax. Sounds bad; IS bad.

In such a case, each time the patient breathes in they will entrain air through the communicating hole in the chest wall (that whole “negative pressure” thing in action). But when they breathe out, instead of having that additional intra-pleural air tidal outwards, the flap will seal it in place; each time they breathe in, the volume of trapped air will increase and you’ll end up with the tension bit.

How much air is required? Well a randomised, prospective, unblinded laboratory animal (porcine) trial conducted by Kotora et al (2013) found that as little as 17.5mL/kg of air injected into the intra pleural space resulted in a life-threatening tension effect.

Actually, that’s a fair bit of air…for those of you who are lazy and don’t want to do the math, that’s 1400mL for an 80kg person. But remember, any tension pneumothorax (open or closed) is progressive – each time you breathe, more air is trapped; therefore, it doesn’t take long to reach crisis levels.

“But are they common enough for us to be worried about?”, I hear you asking. The short answer is yes – in fact, the long answer is also yes.

Kotora et al (2013) reviewed the statistics from the Joint Theater Trauma Registry regarding contemporary combat casualties with tension pneumothorax and found that they accounted for 3 – 4% of all casualties, but 5 – 7% as the cause of lethal injury.

“Yes, but I don’t live in a combat zone…”, I hear you say. I have two responses:

- Good for you; but also,

- According to Littlejohn (2017), thoracic injury accounts for 25% of all trauma mortality. And sure that stat is for all forms of thoracic injury and a sucking chest wound is but one of those but there’s a neat article by Shahani which sums up the incidence nicely and it turns out you should give this some thought.

So, your field craft sucks – now what?

Now that we know that sucking chest wounds are both possible and bad, we should probably discuss treatment.

Some History

Back in the mid 1990’s, Army instructors were very big on rigging up a three-sided dressing. Unwrap a shell dressing, turn the rubbery-plastic wrapper into a sheet and tape three sides down with the open bit facing the feet to allow blood drainage.

And, in an astonishing turn of events, everyone I’ve met who tried this confirmed it didn’t really work that well.

In that Littlejohn paper they make reference to the fact that by the 2004 ATLS guidelines (which are not usually that quick moving), it was being written unblock and white that there was no evidence for or against the three-sided dressing option. It was done because it sounded good in theory, but the evidence wasn’t there.

Now to the New

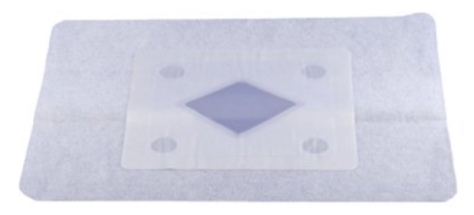

Actually, not that new. Chest seals already existed.

These chest seals (at that time the Bolin produced by H & H Medical, and the Asherman produced by Teleflex medical) included one-way valves to allow for the forced escape of trapped intrathoracic air and blood. basically they took the impromptu three-sided dressing and made it a ready-made device in the form of an occlusive dressing with an integral vent.

But did they work?

Yes and no.

On a perfectly healthy (albeit with a surgically created open pneumothorax) porcine model with cleaned, shaved, dry skin they sealed well and vented air adequately.

However, once the skin was contaminated (dry blood, dirt, hair etc) the Bolin sealed much better than the Asherman. And if there was active blood drainage too (such as in an open haemo-pneumothorax) then all bets were off. Both vents clogged with blood and ceased to work. Sure, you could manually peel the seal back and physically burp the chest but if you did so the Bolin became an un-vented seal and the Asherman was as good as finished (i.e. it wouldn’t reseal). But hey, at least you had sealed the communicating hole and in doing so stopped entraining air.

“Is this the best you can do?” you may be asking. Well to be honest, since the vents didn’t work for more than a breath or two most people decided that the vents were pointless. The outcome was that we all decided to forget about the vents and just seal the wound. That way, assuming that there was no perforation to the lung, this open tension pneumothorax (aka sucking chest wound) became a routine, run of the mill, plain old pneumothorax. And if there were signs of tensioning (e.g. increasing respiratory distress, hypotension, tachycardia….) one just needed to peel back the seal and manually burp the communicating hole thus relieving the pressure. Use a defib pad – those bad boys stick to anything! Problem solved….

Or how about a newer idea + research?

In 2012 the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) started questioning the efficacy of contemporary practices regarding the placement of chest seals on sucking chest wounds. It had already been accepted that the current vented chest seals had ineffective vents, so practice had changed from using a chest seal with an ineffective vent to simple, “soldier proof” unvented seals and burping them as required. Surely there had to be a better way…?

Kotora et al (2013) decided to test three of the most readily available vented chest seals in their aforementioned randomised, prospective, un-blinded laboratory animal (porcine) trial: enter the Hyfin, Sentinal and SAM vented chest seals.

What they found was that all three were effective in sealing around the surgically inflicted wounds and in evacuating both air and blood. Thus, in 2013, CoTCCC changed their recommendations back to the use of vented chest seals.

But there were still some questions:

- Once life gets in its messy way, do they seal (or at least stick to skin)?

- Are all vent designs equal?

To answer question 1, Arnaud et al (2016) decided to evaluate the adhesiveness of the 5 most common chest seals used in the US military using porcine models. What they found was that the Russell, Fast Breathe, Hyfin and SAM all had similar adherence scores for peeling (> 90%) and detachment (< 25%) when tested at ambient temperatures and after storage in high temperature areas when compared to the Bolin. The researchers admitted, though, that further testing was required to assess the efficiency of the seals in the presence of an open tension haemo-pneumothorax.

In response to question 2, Kheirabadi et al (2017) tested the effectiveness of 5 common chest seals in the presence of an open tension haemo-pneumothorax (again, on porcine models). Essentially, there are two types of vent: (i) ones with one-way valves (like in the Bolin and Sam Chest Seals), and (ii) ones with laminar valves (like in the Russell and Hyfin Chest Seals). Their question was: do they both work the same?

What they found was that when the wound is oozing blood and air then seal design mattered. They found that the seals with one-way valves (specifically the SAM and Bolin) had unacceptably low success rates (25% and 0% respectively) because the build-up of blood either clogged the valve or detached the seal. By contrast, seals with laminar venting channels had much higher success rates – 100% for the Sentinel and Russell, and 67% for the Hyfin.

The Summary

So:

- Sucking chest wounds are bad for your health.

- Sealing the wound is good.

- If the seal consistently allows for the outflow of accumulated air and blood, then that’s even better.

Therefore, now that we know all of this, one’s choice of chest seal is important. At CareFlight we use the Russell Chest Seal by Prometheus Medical (and no, we’re not paid to mention them we’re just sharing what we do). Why? Because it works – consistently. Both for us and in all the aforementioned trials.

The premise of this addition to the Collective is that you’re a first responder. That being the case, use an appropriate vented chest seal on a sucking chest wound.

However, you still need to recognise that the placement of the seal does not automatically qualify you for flowers and chocolates at each anniversary of the patient’s survival – you still need to monitor for and treat deterioration. Such deterioration is likely to include a tension pneumothorax for which the treatment is outside of the scope of most first responders (other than burping the wound).

If you are a more advanced provider then your treatments might include the performance of a needle thoracocentesis, or perhaps intubation with positive pressure ventilation and a thoracostomy (finger or tube).

In essence, know the signs and symptoms then master the treatments that are inside your scope of practice. (Or you could enrol in a course…such as CareFlight’s Pre-Hospital Trauma Course or even THREAT… OK that was pretty shameless.)

Meanwhile we’d love to hear:

- What chest seal do you use?

- Why?

- How does it go?

Or you could just tell us what other things you think suck.

Notes:

We’re not kidding about hearing back from you. Chip in. It only helps to hear other takes.

You could also consider sharing this around. Or even following along. The signup email thing is around here somewhere.

That image disparaging all things Kale (or kale) is off the Creative Commons-type site unsplash.com and comes via Charles Deluvio without any alterations.

Now, here are the articles for your own leisurely interrogation.

If you’re time poor and will only read one, make it this one by Littlejohn, L (2017). It’s “Treatment of Thoracic Trauma: Lessons from the Battlefield Adapted to all Austere Environments”.

Another great one (albeit somewhat longer) is by Kheirabadi, B; Terrazas, I; Miranda, N; Voelker, A; Arnaud, F; Klemcke, H; Butler, F; and Dubick, A (2017). It’s “Do vented chest seals differ in efficacy? An experimental evaluation using a swine hemopneumothorax model”.

An oldie but a goodie is this one by Kotora, J; Henao, J; Littlejohn, L; and Kircher, S (2013). It’s “Vented chest seals for prevention of tension pneumothorax in a communicating pneumothorax”.

To round it out, take a squiz at Arnaud, F; Maudlin-Jeronimo, E; Higgins, A; Kheirabadi, B; McCarron, R; Kennedy, D; and Housler, G (2016) titled “Adherence evaluation of vented chest seals in a swine skin model”.

have you ever found a major difference in having a sterile versus non-sterile chest seal? or is it just some marketing thing to make people feel better getting a sterile version? would love your input on this because i can’t find any data right now.

LikeLike

Hi David, interesting question.

I’ve never looked for evidence but when you consider that the skin (and almost always the clothing) is not sterile, then the wound will not be sterile either. Furthermore, my experience is that infections can often be dealt with later – the communicating chest wound requires far more urgent treatment….

….I’ll let you do the math on that one….

Greg

LikeLike