There’s been a lot of stimulating discussion after parts 1 and 2 of this series from Dr Alan Garner (you can check those here and here). Here’s part 3.

Thanks for sticking with the discussion so far. In part 2 we had a look at AP compression injuries and lateral compression injuries. Short summary is binders make sense and there is some observational evidence of benefit in AP compression injuries. However in lateral compression, binders make no biomechanical sense and there is definite evidence they increase fracture displacement both in cadavers and real live trauma patients.

The final group that we have not yet considered in the Young and Burgess classification is the vertical shear group. These patients are complex because the injuries are both horizontally and vertically unstable. You will see what I mean if you have a look at this Xray:

Is putting a binder around the greater trochanters and pulling going to help? Will it produce anatomical realignment? I think you will agree that it is hard to know. In this case it might rotate the left hemipelvis inward and create even more distortion. You might also guess that some traction on the left leg before you apply the binder might get a better result too. More on this later.

Is there any actual evidence that things can get worse with a binder in vertical shear? Tan’s paper had six of this injury type. Two of the six had a fall in MAP immediately after the binder was applied, one by 20mmHg! It is a bit crazy that we are discussing studies with six patients but this is the level of published evidence to date. Such as it is, the evidence is that one in three vertical shear injuries deteriorated immediately after the binder was placed. Toth’s paper found that 14/17 patients had improved alignment post binder in this group so it often does some good. Unfortunately you have to think really carefully about this group, and be prepared to loosen it off again if you don’t get the response you were hoping for.

Yes, loosen it if the patient deteriorates! Primum non nocere. Remember there is as yet no study that has shown significant mortality improvement with pelvic binders. They are not a standard of care. If what you do makes thing worse then backing off is the right thing to do. I try not to let my own psychological need to do everything I can for the critically injured patient in front of me drive me to do things that might actually harm the patient. Sometimes less is more.

So what are we left to conclude?

- AP compression – makes biomechanical sense and low level evidence binders help

- Lateral compression – makes no biomechanical sense and real world evidence binders increase fracture displacement. Is “just holding it still” enough?

- Vertical shear – a really difficult group; evidence of haemodynamic and anatomical improvement in the majority but clinically significant deterioration has also been documented

- The real world as always is a bit more complex than this and mixed injury types happen

- And of course, no evidence yet overall that binders have a significant effect on the outcome that matters in this case –mortality.

It should be pretty obvious that the type of fracture should be the guide to whether or not a binder might help. This is great if you are doing an interhospital transport and have an Xray. Not really helpful though if you are at the roadside, on an oil rig, or at a remote clinic 1000kms from the nearest trauma centre with no imaging (as our teams frequently are). So how can you work out whether a binder will help?

First thing is reading the injury mechanism. If you are at the scene you may get a lot of clues about the force vector, particularly in motor vehicle trauma. This is a photo of an incident I attended a few months ago.

In this case the car had slid sideways into the power pole striking the driver directly in the right side with such force that she had broken the centre console with the left side of her pelvis and was partially in the passenger seat. This can only be a lateral compression injury and there is no way a binder can help. Direct frontal injuries are also pretty obvious and the injury type is going to be an AP compression if a pelvic ring fracture is present.

This is good as far as it goes. It really does not help much with other mechanisms like pedestrians and motor cyclists. Were they side-on or front-on when they were hit by the truck? Motor cyclists can have a significant rotational component to their flight before they hit something which can make prediction of injury patterns really problematic.

There is one other trick which can give you a really valuable clue. Symphyseal diastasis is the hall mark of the AP compression injury. This is the sign that the “book is open”. If you can identify this then you can identify the group that is likely to benefit from a binder to “close the book” (although some will have vertical shear so care is still required). This is yet another use for my trusty companion, the handheld ultrasound.

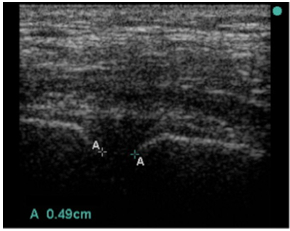

The width of the pubic symphysis can easily be measured with the same high frequency linear probe that you use to exclude a pneumothorax. The upper limit of normal width measured at the point shown in the image is <25mm in adults (Bauman). I am not aware of any published data on children. As with all things there is a bit of variation here and cadaver studies have shown that anterior sacroiliac ligament disruption is likely for displacement greater than 45 mm and unlikely for values less than 18mm. So if the symphysis is less than 18mm you can be very confident the pelvis is not “open”.

Note that in the source study for the reference range they failed to achieve a measurement in one case because the symphysis was wider than the width of their probe. You may have to move the probe from side to side to pick up both sides of a really wide symphysis.

If the patient does not have symphyseal widening on the other hand there is no reason to believe that a binder will help and they may well have an injury type that will be worsened by a binder (the symphysis does not open in lateral compression). Ultrasound is likely to be our best guide as to which patients have the possibility of benefitting from a binder whilst avoiding those where harm is the more likely outcome. Some patients with vertical shear and an open symphysis may still deteriorate so there is no guarantee, but ultrasound will at least allow you to identify the group who have the possibility of benefit rather than harm.

As with so many things in prehospital care we need some good studies in this area. In the meantime, read the mechanism, read your ultrasound screen and be judicious in applying binders. Harm has occurred with these devices – they are not a universal panacea. Much of the art of medicine is picking the right patient for the intervention so you maximise benefit and minimise harm. This patient group is no different.

And thanks for the comments. Julian Cooper’s thoughts helped me work through my own theories on the issues and I have realised that our theories and the observational evidence don’t seem to align. There is also some potential new approaches to the massively haemorrhaging pelvis that are easily applicable in the prehospital environment and those are worth looking at too.

So looks like I am doing part 4. Stay tuned folks.

Reblogged this on PHARM.

LikeLike

GREAT DISCUSSION SERIES AND VERY USEFUL CONCLUDING ADVICE. THANKS FROM THE PHARM!

LikeLike