The excellent Dr Paul Bailey returns to provide more practical insights from the bit of his work that involves coordination of international medical retrieval. This is the second in (we hope) a recurring series which started here.

Greetings everyone, it’s a pleasure to be back for the long awaited second edition of this humble blog. Looking back at my first foray into this unfamiliar world I’m pretty happy with how it reads and I think that it worked out well. If any of you have questions, I’m happy to participate in a bit of to and fro in the comments section.

Where to from here? I thought we might talk about risk. It’s hard to know exactly where to start, but it is fair to say that there are clinical risks, aviation risks, environmental and political risks – and there are probably more but I can’t think of them right now.

Aviation risks are the domain of our pilot colleagues and it’s extremely fair to say that they do a great job. One of the reasons that flying is so safe overall is that pilots specifically (and the aviation industry more generally) take risk very seriously. This might well have something to do with the personal consequences to the pilots of getting it wrong, I’m not sure.

When was the last time, for instance, that the nurses or doctors amongst you had to consider your fatigue score whilst working for a big hospital? What is the mechanism by which you might stop work when you consider yourself impaired or too tired to work any longer? Random drug testing at work anyone? If you’re a doctor or nurse, not likely, unless you are also working in aviation. See what I mean?

Whilst on a job the clinical team are considered part of the crew and whilst it is certainly within our job description to point anything out to the pilots that looks odd – it is up to the pilots to get us there and back safely. One of the Gods of CareFlight said to me once that it was his considered opinion, having been in the game a while, that if the pilots don’t want to go somewhere – for whatever reason – then neither does he. I reckon that is a pretty good rule of thumb.

What about medical risk?

Preparing for an international retrieval, the risk assessment starts straight away. From the Medical Director’s chair, we attempt to have a clinical discussion with SOMEONE close to the patient, usually a doctor or nurse in the originating hospital. This can be difficult – sometimes there are language issues; sometimes standards of care might be different to what we are used to; sometimes it’s just the time of day. How many people would be able to give a comprehensive medical handover at short notice in your hospital at 02:30?

We can also discuss the case with a nurse or doctor from the assistance company as an alternative. Sometimes it is even possible to talk to the patient or their relatives and in fact this is often the best source of up to date information.

In a similar way, patients’ clinical condition can change in the substantial lead time between the activation of a job, your arrival at the bedside and the eventual handover of the patient to the next clinical team.

In the world of international medical retrieval, if the patient is still alive by the time you get there, it is likely that they are in a “survivors” cohort already and will very likely make it to the destination hospital intact. If death was considered imminent, it is unlikely the assistance company would go to the lengths of setting up an international medical retrieval. Sepsis is probably the grand exception to this rule – patients who are septic have progressive illnesses that are not improved by being shaken up in the back of an aircraft.

The summary is that sometimes the information is incomplete, may be in fact be wrong in spite of the best efforts of the Medical Director, or may well have been correct at the time but things have moved on. It’s best to keep an open mind about what you are going to.

Ways to Ruin a Dinner Party – Bring Politics and the Environment

Easy to understand in some ways, and hard to define on paper are the environmental and political risks associated with international medical retrieval.

Some locations are potentially dangerous on a 24/7 basis and it can be a matter of choosing the “least bad” time of day – eg daylight hours – for you to be on the ground, and to make that period of time as short as possible – eg by arranging the patient to meet you at the airport. Sometimes the situation will require the assistance of a security provider. Port Moresby would be an example of a location where any or all of the above statements are true.

Different standards apply in some locations and it can, for instance, be necessary for all fees and charges associated with a patient’s hospitalisation to be paid prior to their departure. Retrieval team as bill settlement agency. Indeed, sometimes these fees can be very complex and quite difficult to understand. The hospital administrators may not be sympathetic to your timeline with regards to pilot duty hours and a strong wish to depart.

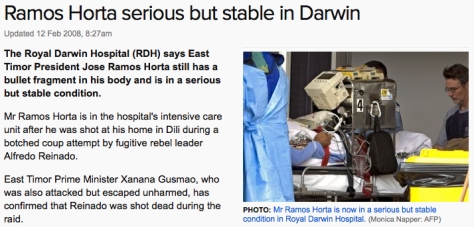

Some counties in our region have relatively new or potentially unstable political situations and this might come into play from time to time. East Timor is a perfect example. It is also possible to find yourself in the thick of a countries political situation in the event that a government official or politician becomes unwell and requires evacuation to a location with a higher standard of medical care.

So the risk is there, what do you do?

In the end, it is not possible to control for everything that could go wrong on a retrieval. The essentials are to be well trained, have the right equipment with you (it’s not much use back at the base), work with good people all of whom are doing their jobs properly and keep an open mind about both the clinical and logistical situation as the case progresses.

So here are some principles we try to follow from the coordinators end:

- We will not send you to an uncontrolled situation.

- We will endeavour to have you flying in daylight hours wherever possible.

- We will do our best to give you a comprehensive medical handover prior to departure and discuss things that might go wrong.

- The pilots undertake to get you and the patient there and back safely.

And my suggestions for those on the crew?

- It is vital to maintain situational awareness and to understand that the world of international medical retrieval is fluid and things change – you don’t have to like it but you do need to respond.

- Good communication is essential – within the clinical team, between the clinical team and the pilots and between those on the mission and the coordinator (not to mention the local organisers). Good communication is your best friend and keeps you, your team and the patient safe.

Until next time …