Somewhere around Sydney at the recent ANZCA Annual Scientific Meeting, Dr Andrew Weatherall had the chance to kick along a discussion about trauma in kids. This is the post version of things covered and things in the chat. This is also cross-posted over at the kids’ anaesthesia site.

Let’s start by keeping in mind a very, very important point: it’s probably not possible to find anyone near a conference meeting room in Sydney on a Thursday who is likely to be a true expert in paediatric trauma, particularly in anaesthesia. True paediatric trauma experts, the ones who know the literature backwards and have an amazing array of personal experiences that have refined their approach, are a rare, perhaps even non-existent, species.

That’s not a statement trying to offer up an excuse or throwing shade anywhere else. It’s just stats. If you look at the most recent Trauma Registry report out of NSW, our most populous state in Oz, you’ll get a chance to look at the 2015 collated serious trauma stats. For the whole of that year, across the whole of the state, there were 225 kids who got to hospital with serious injuries. 225 across the three kids’ trauma centres. Now spread that across all the people who work there and ponder how many people are likely to get the sort of exposure to get really good.

There just can’t be that much exposure. And if people tell you they see heaps, well, I reckon they probably don’t.

Which I guess means that everything that follows here should be held up to really serious scrutiny. Check the references. Size it up. See if it holds water. Add another cliché here.

The attendees at this session came from a variety of anaesthetic backgrounds from the level of student to very experienced. For most of them the main theme seemed to be ‘I don’t really feel comfortable with kids’ trauma [“Phew,” I thought, “me too”] and I don’t really get to see it much. But when I do it’s usually bad.’

This is common in lots of places. In NSW, prehospital organisations are directed to drive past hospitals and go on to a designated kids hospital with an injured child they’ve picked up unless they genuinely think that child is about to die. So if they pull up at your joint, it’s bad.

The aim here is to start with a story. In that story we’ll get to cover a range of things about kids’ trauma. It probably won’t be earth shattering. It should be practical.

So let’s get to it.

The Place

Let’s start with a standard day at your local anaesthetic joint. It’s your favourite hospital at Mt Anywhere. Like most Australian “mountains” it is, in fact, a very poor excuse for a mountain and actually “Anywhere” is really “somewhere”. I’m just being vague about the somewhere.

Let’s say it’s a solid-sized place on the edge of a metropolitan area. There is plenty of adult surgery, the occasional elective paediatric list of some sort. The place has a neurosurgeon but not necessarily continuous coverage and big kids’ stuff goes elsewhere.

You get a call from the ED because they have received a call just a few moments ago. A prehospital crew out there somewhere near Mt Anywhere have picked up a kid. This kid is 6 years old and thought to be about 26 kg. They have had an altercation with a dump truck. Ouch.

The initial assessment is that this kid is pretty unconscious with a GCS of 6, which seems not that surprising because there is a fair bit of swelling around the left eye like they took a hit. Their heart rate is 128/min, they have a blood pressure of 95 mmHg systolic. Happily when they checked peripheral saturations they were in the high 90s and they can’t find anything on the chest. They added oxygen anyway. They also placed an intraosseous needle. They are on their way. You have 10 minutes.

Big Question Number 1

So at this point the question I asked was “What are you worried about?”

I think the response was “It’s a kid. Everything.”

And then more seriously:

- There were worries about the injuries themselves. Head injury was thought to be likely. The heart rate might point to bleeding somewhere and kids can compensate for a bit before they fall off a cliff.

- There were some who were worried about their ability to do technical things in kids. Challenging at the best of times if you’re not doing it regularly, everyone was pretty unanimous that the situation was unlikely to elevate their performance.

- What can we do here?

This last one was an excellent point. A kid with big injuries should ideally be going somewhere dealing with critically ill kids all the time. If you think there’s a good chance they’ll have to go elsewhere there should be absolutely no one in the system who would mind if you called retrieval before the patient even arrives so they can start thinking about plans. You might even find they have useful ways of supporting you and they can get things rolling if retrieval will be needed.

Arrivals

The patient turns up and they are basically as advertised. The obs are the same. The left upper arm looks wrong enough that you’re thinking “that’s a fracture”. The patient is a bit exposed and there’s some bruises down the left side of their abdomen.

Question 2 is pretty obvious; “what first?”

Or perhaps the better way to phrase it is “What next (and how is it different because it’s a kid)?”

The discussion pretty much came down to the following (there’s a bit of abridging here):

- ‘I’d use the team to assess and treat with an aim to get as much done at the same time as possible.’

- ‘I’d assess the airway and maintain C-spine precautions.’

- ‘I’d assess breathing and treat as I needed to.’

- ‘I’d get onto circulation, try to get access, and if I needed fluids try and make it blood products early rather than lots of crystalloids.’

- ‘I’d make sure we complete the primary survey and check all over…’

Now, you probably noticed that all of these things are just the same things as everyone would say for adults. Maybe it turns out they are just litt… wait, I’m not supposed to say that.

There’s a point worth noting though. If you are going to have to face up to kids’ trauma and there are things that worry you, it’s also worth noting the stuff that is close to what you are more comfortable with. There will always be basics you can return to.

Now the discussion did touch on things around the topic of how you’d go about induction of anaesthesia and intubation. There were no surprises there with a variety of descriptions of RSI with agents that people felt they were excellent at using. A whole thing on that seems like too much to go with here but you could have a read about RSI in kids at this previous post.

Likewise THRIVE (and other forms of high flow nasal prong work) was mentioned. That’s probably beyond the scope of this post too if it’s going to stay under a bazillion words but it’s worth pointing out a couple of things that are also in this thing here and here. One is that the research that has been done that’s kind of relevant to extending apnoeic oxygenation hasn’t been done in an RSI set up and the nasal prongs aren’t generally applied during the actual preoxygenation bit.

Where to from here?

Now it’s probably time to move this along so let’s say that heart rate has improved a little to 115/minute, the blood pressure is about the same and you’ve assessed all those injuries and think facial fractures are on the cards, plus a fractured left humerus.

Oh, I should have mentioned that left pupil. The one that’s big and not doing much. The one I deliberately didn’t mention until now because I didn’t want the thing to move too quickly.

This brings us to a crucial and very deliberately placed point – what sort of imaging are we going to do?

We’re going to bench FAST as a super useful option here because the negative predictive value is somewhere around 50-63% (from the Royal College of Radiologists document) and we’re moving to a cashless society so coin tosses seem old school.

Let’s assume we’re heading to the CT scanner because there is no neurosurgeon around who doesn’t want a scan to make a plan. So how much do we scan?

I threw this to the room and there was a variety of options offered. The classic Pan Scan was mentioned. Or just the head. Or maybe head and neck. Or head and neck and abdomen but maybe not chest.

Finally we get to something that really is different in kids then. In kids the threshold for exposing the patient to radiation is a bit higher than in adults. This is because the risks of dosing kids with radiation during scans are far more significant than for adults. The ALARA principle (“As Low As Reasonably Achievable”) comes very much into play here. You can find a bit more description about this here or you can look at the Royal College of Radiology guidelines.

The headline things to remember are that if you expose a kid to 2-3 head CTs before they hit the age of 15 it looks like it might almost triple the risk of brain tumours. Make it 5-10 and that’s triple the risk of leukaemia. Abdominal and pelvic CTs give you a higher dose of radiation.

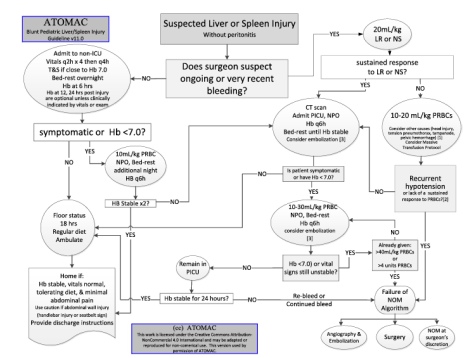

So in this context in kids there is a real second thought about what scanning to do. On top of that for things like abdominal trauma it’s much more likely in kids that the surgeons will pursue non-operative management. And while there are probably better places to delve into the minds of surgeons it’s worth spending a moment with the flowchart from the ATOMAC guidelines to try and get a sense of their thinking. Or if you look at it long enough I think it works like one of those 3D eye pictures.

What is definitely the case is that treating abdominal injuries on the basis of the grade of injury as demonstrated on scanning (for spleen and liver injuries particularly) isn’t really a thing. Early decisions are based very much on haemodynamics and clinical assessment.

So in our patient where there isn’t current clinical evidence of intra-abdominal pathology (just trust me, there isn’t) and the haemodynamics aren’t suggesting hidden pathology, then the scanning is probably just going to be looking at the head and maybe cervical spine. Plus this patient is going to start with a chest X-ray (particularly after intubation).

Lo and behold, the CT head shows a left subdural haematoma with a bit of midline shift. Time to go here…

The Goalposts

Off to theatres then and I guess the next question is:

- What are the priorities for the anaesthetist here?

Everyone pretty much jumped on two:

- Get on with it – meaning the thing that needs to happen to protect brain tissue is the surgeons need to do a thing. There’s not much the anaesthetists can do that will help brain tissue as much as the drilling bit in this context. Delaying for things that’d be ideal (say, an arterial line) is not really what the patient would ask for. So ‘hop to it’ was a universal endorsement.

- Make sure you are giving the brain the best odds of scoring blood supply.

There was passing discussion on agents, where to have the CO2 levels, hypertonic solutions and things like that but really most of those are as per adults so people zeroed in on perfusion targets.

In kids this is a bit of a problem because there is even less good evidence compared to the adult population. This is particularly the case for blood pressures before you have access to intracranial pressure monitoring and can therefore figure out the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). On top of that the Brain Trauma Foundation TBI guidelines have recently been updated, but not for kids. That document still lives on from 2012 (at least for now).

When I went to check on the targets listed at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, their CPP targets went like this:

- > 10 years old aim for 60 mmHg CPP or above.

- In the 1-10 year old age range aim for CPP 50 mmHg or above.

- In the under 1s aim for 45 mmHg or above.

The thing is, at least when you start you probably won’t have access to intracranial pressure (ICP) to do the CPP = MAP – ICP (or CVP if that’s higher) calculations. Hence this suggestion that you should treat for a bad case scenario where ICP is assumed to be 20 mmHg because that’s when you’d step in and do something about it.

In this case you need to add 20 to your mean arterial pressure (MAP) and aim for that target. What would be kind of nice of course is having a systolic BP target. Unfortunately we don’t get that until the age of 15, where the new TBI guidelines suggest you should keep SBP above 110 mmHg.

As an aside I have some reservations about the ‘let’s just assume ICP is bad’ because assumptions seem like not the best basis for manipulating physiology. They seem even worse when you’re making a lot of assumptions about how pathophysiology will play out.

Given that TBI is associated with disruptions to the blood brain barrier and a variety of other stresses, assuming that raising MAP won’t just result in swelling, bleeding into vulnerable areas or other causes of general badness seems … fraught.

For now it’s all we’ve got though so there it is.

The Red Stuff

The surgeons do their thing of course and that means (particularly when you have certain topics to cover in a conference session) lots of bleeding. There are bigger places to go into massive transfusions in kids here, but it’s worth noting a couple of key tips:

- Massive Transfusion Protocols help and emphasise the need for not just the red stuff but good amounts of a fibrinogen source (locally that’s cryoprecipitate rather than fibrinogen complex concentrates, platelets and FFP. A quick Google search will find the guideline used at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and the breakdown of what comes first…

and what comes next…

- The number for pretty much all of the units (at least to start with) is 10 mL/kg. Quickly figuring out how much 10 mL/kg is for the patient in advance makes the calculations a lot quicker.

- Of course the one different one is cryoprecipitate which is around 1 unit per 5 kg (up to 10 units).

- Calcium replacement shouldn’t be underestimated as an ally (or even necessity). Perhaps me ending up mostly looking after kids just coincided with everyone getting interested in calcium, but I lean on this way more than I used to, particularly as the things that are supposed to help you clot go in.

Of course you’re not allowed to talk about trauma without mentioning tranexamic acid (TXA) because we’d all like to make sure there’s at least a little less bleeding if there’s a way we can influence it. So we want to get it there and get it here quickly.

The main question then is how much should we be giving?

Getting Bitten

The one guideline out there is the one from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Back around 2012 they came up with a “pragmatic dosage” of 15 mg/kg as a loading dose then 2 mg/kg/hour.

I can sort of see why because there’s not a huge amount of evidence out there for ideal dosing in kids, particularly in trauma. What we end up with is evidence from other settings where traumatic damage is inflicted on tissues (i.e. big surgery).

If you go to any of those settings, like craniosynostosis surgery or scoliosis surgery or cardiac surgery, you’ll see a dizzying array of dosing regimes too. Loading doses of 10, 20, 30, 50 and 100 mg/kg with infusions any of 2, 5, 10 and 20 mg/kg/hr. This only makes figuring out what to do an awful lot harder.

So when they came up with that “pragmatic dosing” they went for a pretty cautious option. That’s partly because they’re not super sure about risks of thrombosis and there’s lots of concern about seizures with TXA loading. The theory goes that with higher doses you get higher levels of TXA in the CSF and that leads to inhibition of inhibitory glycine and GABA receptors (because they have those crucial lysine binding sites). It’s not everything but there’s at least some cohort research suggesting there’s not much association. In a retrospective study looking at craniosynostosis surgery with 1638 records examined the rate of seizures was the same across groups at around 0.6%.

The problem with that dosing option is there’s enough evidence to suggest that 15/2 is just not going to cut it. You might as well get a mosquito that bit a person who once had TXA and get them to sneeze on your patient. Bigger doses seem likely to work better.

A relatively recent paper in scoliosis surgery patients compared higher dose TXA with a lower dose. In this case the higher dose meant loading at 50 mg/kg then an infusion of 5 mg/kg/hr while low dose meant loading at 10 mg/kg then infusion at 1 mg/kg/hr.

So was there a difference? Well the lower dose crew lost an average of 968 mL and needed 0.9 units of red cells on average. The higher dose crew ended up losing about 695 mL and receiving 0.3 units of red cells on average. Unfortunately there was only 72 patients in the lower dose group and 44 in the higher dose group. So we’re left with not much.

There’s enough to suggest though that higher doses are probably required to actually influence the fibrinolytic pathway. A dose of 20-30 mg/kg to start with is much more like what I’d do (without exceeding 1 g) followed by an infusion of 10 mg/kg/hour.

The Next Bit

Look, don’t you think this has gone on long enough? Everyone did great, the surgeons operated really well and everyone got through a tough day pretty well and gave our imaginary patient the best shot possible.

There were of course other things we chatted about. Things like tricks for getting that IV access (if you remember the name Seldinger and that a 0.018” wire will fit up a 24 gauge cannula you’re in good shape). Then the challenges of spine immobilization and the role of options other than a hard cervical collar. Then of course the importance of considering the impact on ourselves when we look after these kids.

None of those deserve short change though so that can wait for some other time. Or maybe there’s an expert out there for that.

Notes:

The things on radiation risks in kids to look at would be this one:

and this one:

Then of course there’s the bigger Royal College of Radiology Guidelines.

Oh, and the ATOMAC guidelines would be these ones:

Here are those Brain Trauma Foundation TBI Guidelines.

The kids TBI guidelines are here.

I can save you the Google search when it comes to that Massive Transfusion Protocol.

That RCPCH document about TXA in trauma is this one.

The thing in craniosynostosis surgery that covers seizure risk is this one:

The high-dose vs low-dose scoliosis study is this one: