Well this time around we welcome a new contributor. Dr Shane Trevithick is a retrieval doctor with many years experience covering prehospital, interhospital and coordination work when he’s not being an emergency doctor. He’s got a bit on simple systematic approaches that get the job done.

One of the exciting things that practicing medicine out of a helicopter does is make you a “Rock Star” of the medical world. Your colleagues and the general public are amazed by your method of arrival on scene, the ensuing dramatic interventions, the sexy uniform, your appearance on the evening news and your general confidence back in the hospital when you can manage dramatic medical problems which seem much easier when they are not trapped upside down in wreckage.

The problem with being a Rock Star performing in a band is that to continue being the Rolling Stones of Medicine [Ed: we would not suggest this reference is in any way a sign of author age] you feel compelled to keep releasing new albums regularly. This can be a problem, especially with social media, as developments in medicine do not keep pace with the need to tweet and podcast and you are at risk of grabbing the latest study or technique involving patient plumbing and announcing this to the world as the next big thing in the world of Helicopter Rock Band Medicine.

This does tend to mean that you can gloss over some of the basic things which really make a difference to your medicine and your patients. Just like a Rock Star will be completely familiar with the basic things that makes playing their instrument possible, it helps if you can really nail the basics.

So here are a few tips that work for me to do a better job as a retrievalist in whichever team I’m working in.

Have a Plan

A good plan when you approach a patient makes a big difference, especially for an interhospital retrieval. This makes a huge difference to the smoothness of how your retrieval will flow and reduces your risk of making an error by omitting something. This is a bit like having a checklist but I don’t quite use it like that because really a checklist involves a bit of call and response. It’s not quite a strict list, more like having a systematic approach to reduce the risk of error. If you have the same pattern to how you do things you get much quicker and slicker and you are much less likely to miss something.

It took me a lot of years to work out I didn’t have a consistent system. And when I analysed some the mistakes and complications I had I realised they came about because, like a good anaesthetic registrar would, I modified what I did to fit the Paramedic I was working with, rather than communicating a system that would ensure I didn’t miss things. If I had actually had any system to do the job myself then I would have avoided a lot of problems.

So here’s the system I created for myself. It might work for you, or might just prompt you to think through what system would work best for your brain.

A: Airway

- Check ETT Size and measurement at a fixed point (e.g. teeth).

- Check ETT Security – that means connections and how well it is tied/taped. I almost always find myself fixing something about security.

- Check ETT Site – on an X-ray.

B: Breathing

- How well is the patient breathing? It’s a seemingly simple step but yes, I still remind myself.

- What are the ventilator settings? Got it, now match them (with the transport ventilator). I tend to work with paramedics who make logistics and practicalities in a brilliant fashion. It always seems that just as I get this step done they are ready with a patient slide to transfer the patient onto the stretcher.

C: Circulation

- What’s the IV access? Secure that well too.

- What about the arterial line? Critically ill patients being moved should have this so now is the moment to make sure it’s connected, working and zeroed. This usually matches up with when my friendly paramedic is miraculously also up to the exact bit where I should be helping with the monitoring.

D: Drugs

- Think “I need enough sedation for 3 times the anticipated length of transfer” and make sure you’re ready (plus see the bit below).

- Also have a think about what things you have handy as downers (mostly sedation and analgesia) and uppers (like metaraminol) which might just come in handy if you get the downers bit not quite right (or for other reasons of course).

E: Everything Else

- Do you have all the equipment you brought with you?

- Do you have the notes?

- Do you have any scans?

- Do you have ALL the equipment you brought with you?

- Do you have any patient belongings, either the material ones or the relatives that also belong to them that you might be bringing?

- No, really, do you have ALL the equipment?

Now, about that sedation

Yes, I gave this its own bit because it is really important. Let’s assume you’re highly skilled at drug-assisted intubation. After that there is the post intubation phase, whether you have intubated the patient yourself or whether the patient comes already intubated.

I think it is really important to make a couple of distinctions in retrieval. One is you are giving “a Retrieval” and NOT “an Anaesthetic” or “a Sedation”. An Anaesthetic is an art form so important there is an entire medical specialty devoted to it. But it is basically focussed on having someone pain free, unconscious of what item number is being performed on them, and then woken to a state of bliss in a a calm quiet environment surrounded by nurses fussing over you. Usually woken relatively quickly after the item number as well.

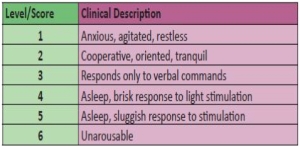

This does not apply to retrieval. In a retrieval you do not want your patient to wake up. Especially over that last speed hump on the roads leading to the hospital. With apologies to ICU that your retrieval patient will take a day longer to wake up than someone they lightly sedated you have to remember it is not a “sedation” it is a “retrieval”.

There is very little fussing (doctor dependant) and a lot of shaking up/moving/noise/vibration/stimulation. When I was a retrieval registrar no one discussed this with me and since I was very comfortable to treat people with morphine and midazolam either together or separately, with propofol, (ketamine hadn’t come into use again when I was a registrar) and with fentanyl I just kept running whatever the hospital had chosen assuming that since they were a hospital they had correctly chosen the right sedation for the right patient. It was also quicker and easier to just keep running whatever they started as we didn’t have to go through the entire fuss of drawing up new drugs.

I am now, with experience, absolutely sure that this is not best practice. Now I don’t use propofol at all for a retrieval – it is an ideal anaesthetic drug which makes it very poor for A Retrieval. Of course that is only my opinion born of experience with no published data I am aware of (there is a study for someone) however I can promise you that performing a “retrieval” after intubation requires only two drugs for maximum benefit: Separate infusions of fentanyl and midazolam. If you are running two inotropes and only have one pump left I will allow you to mix them together but the ideal concentrations are 1000mcg fentanyl in 50mL and 50mg of midazolam in 50mL. Run them at 10x higher doses than you would use in ICU so you need to think about starting at 200-400mcg/hr fentanyl and heading north and 5-10mg/hr of midazolam.

And if you arrive and your patient is light and coughing on the tube, if their haemodynamics will tolerate it just give them substantial loading doses of these drugs, say 0.1mg/kg midaz and 2mcg/kg fentanyl and then start your high dose infusion. I can promise you this will be the best tolerated, most cardiostable way of performing “A Retrieval”.

Just remember the gotcha – as your helicopter starts to land at the hospital it will shake violently for 30 seconds or so. This will cause your patient to wake up and extubate themselves at the one time you can’t go out of your seatbelt to fix the problem. Remember to bolus before landing.

So there you go. Some of the basics that can help you be the Rock Star you want to be.

Notes:

All the images here are via Creative Commons on flickr and are unchanged here and put up by Izzy by the Sea, Duncan C, ThoreauDown and Bart Everson.

If you have suggestions for future posts hit us up. And if you like the stuff around these parts, you could always consider sharing or signing up to receive emails.