In times where external standards are increasingly applied to health services, where does retrieval medicine fit in? Dr Alan Garner shares his insights after wrestling with the Australian National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards process.

In Australia, national reform processes for health services began in the years following the 2007 election. Many of the proposed funding reforms did not survive negotiation with the States/Territories but other aspects went on to become part of the Health landscape in Australia.

Components which made it through were things like a national registration framework for health professionals. Although the intent of this was to stop dodgy practitioners moving between jurisdictions, the result for an organisation like CareFlight was that we did not have to organise registration for our doctors and nurses in 2, 3 or even more jurisdictions as they moved across bases all over the country. Other components that made it through were the national 4 hour emergency department targets although I think the jury is still out on whether this was a good thing or not.

Other Survivors

Another major component to survive was the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. The idea is that all public and private hospitals, day surgical centres and even some dental practices must gain accreditation with these new standards by 2016. The standards cover 10 areas:

- Governance for Safety and Quality in Health Service Organisations

- Partnering with Consumers

- Preventing and Controlling Healthcare Associated Infections

- Medication Safety

- Patient Identification and Procedure Matching

- Clinical Handover

- Blood and Blood Products

- Preventing and Managing Pressure Injuries

- Recognising and Responding to Clinical Deterioration in Acute Health Care

- Preventing Falls and Harm from Falls

Are these the right areas? Many of the themes were chosen because there is evidence that harm is widespread and interventions can make a real difference. A good example is hand washing. Lots of data says this is done badly and lots of data says that doing it badly results in real patient harm. This is a major theme of Standard 3: preventing and controlling healthcare associated infections.

![Here is a visual metaphor for the next segue [via www.worldette.com]](https://careflightcollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/viaduct-copy.jpg?w=474&h=314)

What about those of us who bridge all sorts of health services?

So what about retrieval? We are often operating as the link between very different areas of the health system. And we pride ourselves on measuring up to the highest level of care within that broader system. So do these apply to us? Did they even think about all the places in between?

Well, whether these Standards will indeed be applied to retrieval and transport services remains unclear as retrieval services are not mentioned in any of the documentation. CareFlight took the proactive stance of gaining accreditation anyway so that we are participating in the same process and held to the same standards as the rest of the health system.

So when we approached the accrediting agency, this is what they said: “Well, I guess the closest set of standards is the day surgical centre standards.” We took it as a starting point.

Applying Other Standards More Sensibly

This resulted in 264 individual items with which we had to comply across the ten Standards. And we had to comply with all standards to gain accreditation – it is all or nothing. However as we worked through the standards with the accrediting body it became clear that some items were just not going to apply in the retrieval context.

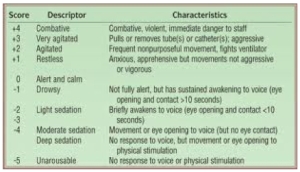

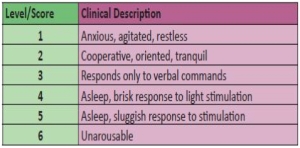

A good example is the process for recognising deteriorating patients and escalating care that is contained in Standard 9. There are obvious difficulties for a retrieval organisation with this item as the reason we have been called is due to recognition of a patient being in the wrong place for the care they need. This is part of the process of escalating care. It would be like trying to apply this item to a hospital MET team – it doesn’t really make sense.

With some discussion we were able to gain exemptions from 40 items but that still left us with 224 with which to comply. Fortunately our quality manager is an absolute machine or I don’t think we would have made it through the process. There’s take away message number one: find an obsessive-compulsive quality manager.

It took months of work leading up to our inspection in December 2014 and granting of our accreditation in early 2015. Indeed I am pleased to say that we received a couple of “met with merits” in the governance section for our work developing a system of Carebundles derived from best available evidence for a number of diagnosis groups (and yes I’ve flagged a completely different post).

So yes or no?

Was the process worth it? I think independent verification is always worthwhile. As a non-government organisation I think that we have to be better than government provided services just to be perceived as equivalent. This is not particularly rational but nevertheless true. NGOs are sometimes assumed to be less rigorous but there are plenty of stories of issues with quality care (and associated cover-ups) within government services to say those groups shouldn’t be assumed to be better (think Staffordshire NHS Trust in the UK or Bundaberg closer to home)

As an NGO however we don’t even have a profit motive to usurp patient care as our primary focus. The problem with NGOs tends rather to be trying to do too much with too little because we are so focused on service delivery. External verification is a good reality check for us to ensure we are not spreading our resources too thinly, and the quality of the services we provide is high. The NSQHS allow us to do this in a general sense but they are not retrieval specific.

Is there another option for retrieval services?

Are there any external agencies specifically accrediting retrieval organisations in Australia? The Aeromedical Society of Australasia is currently developing standards but they are not yet complete.

Internationally there are two main players: The Commission for Accreditation of Medical Transport Systems (CAMTS) from North America and the European Aeromedical Institute (EURAMI). Late last year we were also re-accredited against the EURAMI standards. They are now up to version 4 which can be found here. We chose to go with the European organisation as we do a lot of work for European based assistance companies in this part of the world and EURAMI is an external standard that they recognised. For our recent accreditation EURAMI sent out an Emergency Physician who is originally from Germany and who has more than 20 years retrieval experience. He spent a couple of days going through our systems and documentation with the result that we were re-accredited for adult and paediatric critical care transport for another three years. We remain the only organisation in Australasia to have either CAMTS or EURAMI accreditation.

For me personally this is some comfort that I am not deluding myself. Group think is a well-documented phenomenon. Groups operating without external oversight can develop some bizarre practices over time. They talk up evidence that supports their point of view even if it is flimsy and low level (confirmation bias) whilst discounting anything that would disprove their pet theories. External accreditation at least compares us against a set of measures on which there is consensus of opinion that the measure matters.

What would be particularly encouraging is if national accreditation bodies didn’t need reminding that retrieval services are already providing a crucial link in high quality care within the health system. There are good organisations all over the place delivering first rate care.

Maybe that’s the problem. Retrievals across Australia, including all those remote spots, is done really well. Maybe the NSQHS needed more smoke to alert them.

For that reason alone, it was worth reminding them we’re here.